It has been over eighteen months since I attended a workshop and introduced to the Flipped Classroom. The presenter discussed the ability of her Mathematics students to stop, pause and rewind her teaching around a particular concept. We watched a short video of her class in action - the students were engaged, active and mentoring one another by practicing the content the teacher had presented in class time. The concept of watching video content to learn or understand something was not foreign to me. Just a week earlier I had taught myself how to reconnect the tie cord on my lawn mower after it had fallen off!

I left the presentation reflecting on the benefits of this shift in teaching time and space and how I could get it underway with two classes as a trial. I was also aware that this would not be a miracle panacea for my teaching and also decided to delve deeper into this pedagogy by completing research into Flipped Learning through the University of Canterbury.

https://goo.gl/ZHndXH

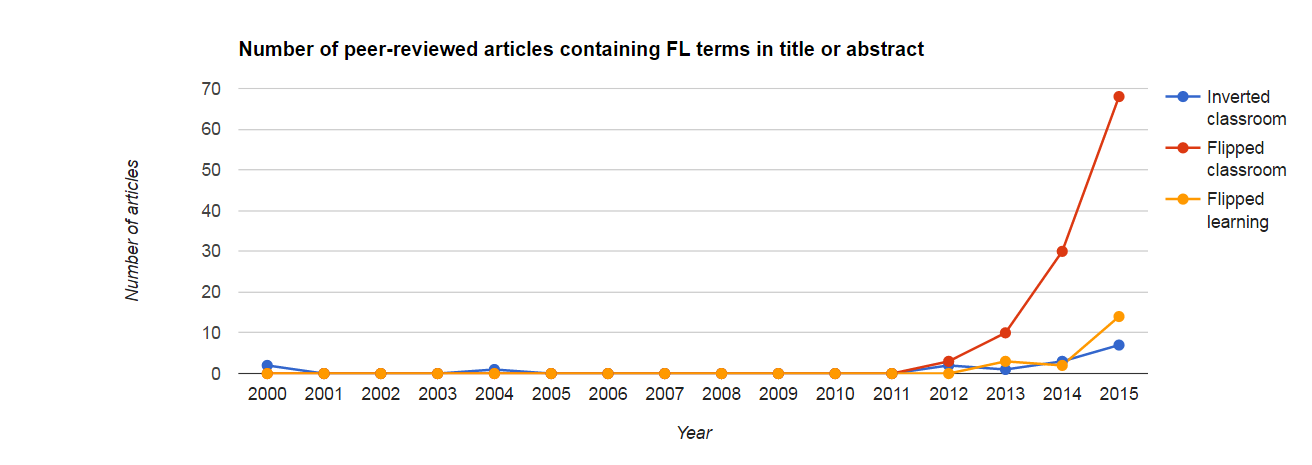

A question that often comes up when discussing Flipped Learning is that there is no definitive research or data that demonstrates its effectiveness. I would begin by stating that the body of peer reviewed literature into Flipped Learning, Flipped Classroom and Inverted Classroom is small however, it is growing at an exponential rate. In an analysis completed by Robert Tolbert, 38 articles were written in the first half of 2016 for Flipped Learning, Flipped Classroom or the Inverted Classroom. In the image below you may notice a sharp spike in 2012. It coincides with the year Jon Bergmann and Aaron Sams released their book ‘Flipping your classroom’. If you continue to hear there is no research basis for Flipped Learning - this is simply not true. There is a rapid shift in the amount of research and scholarship being produced on this pedagogy. Take a look at this bibliography I have compiled for you to have a look at the range of studies that have been completed.

https://goo.gl/HgqWIY

In this post I will outline four benefits and an opportunity to develop in the Flipped Classroom approach. It is important that we encourage awareness of cases where the Flipped Classroom approach did not work. Doing so allows us to continue to develop and refine the Flipped Classroom approach rather than declaring victory too early.

https://goo.gl/bcBRxT

Increase in Personalised Learning

At the center of Flipped Learning is its focus on individualizing learning. Class Time is spent focusing on problems, questions, inquiry and project based learning (Roach, 2014, Halili & Zainuddin, 2016, Lage, Platt & Treglia, 2000). This enables time for teachers to help students stuck on a difficult concept or a problem that traditionally is completed during homework time (Bergmann & Sams, 2014, Hung, 2015, Straw, Quinlan, Harland & Walker, 2015). In a traditional classroom, this interaction would not occur as often because teachers spend the bulk of their time lecturing content. In this model the teacher becomes a, “facilitator and students become the focus of the class.” (Talley & Scherer, 2013, p. 340) Flipped learning has been identified as one of the most promising approaches to transforming learning for our students (Hung, 2015). It encourages students to take responsibility for their learning and to, “learn at their own pace and to make faster progress than would otherwise have been the case.” (Straw, Quinlan, Harland & Walker, 2015, p. 4). Little research has been completed on the impact of Flipped Learning however, the sheer number of teachers that have reported successful implementation of the strategy provides evidence of its powerful use as an instructional method (Enfield, 2013). Students across studies have shown the ability to interact with content that suits their learning style, allowing the teacher to have a greater insight into student understanding, resulting in increased interaction with students (Peters, 2015, Enfield, 2013, Roach, 2014).

Increase in Engagement and Ownership

Recent case studies of Flipped Learning discuss the benefits of increased learner agency and their ability to manage their learning. Due to the range of technology available to students it has increased their ability to have greater autonomy of their learning and when they complete this learning. A recent study completed by Waikato University, into a first year Engineering class, found that, “90% of students appreciated learning in their own time and 84% at their own pace.” (Peters, 2015, p. 6). This skill of autonomy and independent learning is significant to Flipped Learning and could be, “appropriate for preparing students for a 21st century career that will require continued on job learning.” (Enfield, 2013, p. 25). Within a trial of nine schools in England and Scotland, teachers noted that students were more willing to learn for themselves and this helped them developed a positive work ethic (Straw, Quinlan, Harland, Walker, 2015). Flipped Learning enables more time for learning where students can apply their knowledge in labs, problems and tasks, requiring students to use the higher order skills of Bloom’s Taxonomy (Bergmann & Sams, 2014, Talley & Scherer, 2013, Hung, 2015, Love, Hodge, Grandgenett & Swift, 2014). Students’ curiosity is triggered, developing their, “tactile memory of speaking, discussing and solving problems with their classmates instead of the basic learn and recall that traditionally happens.” (Roach, 2014, p. 78). As noted by students across many studies; the more interactive the class environment meant the more likely they were to be focused and engaged with their learning.

Anywhere & Anytime

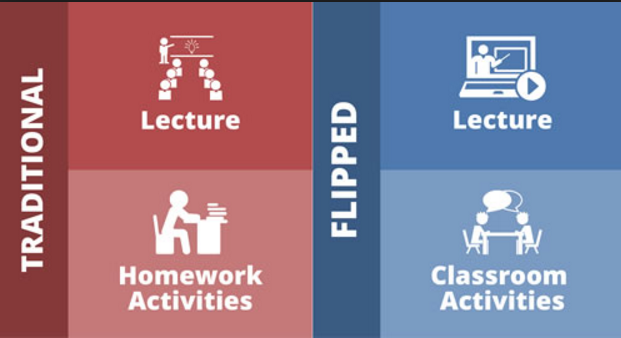

The notion of Flipped Learning is a grassroots teaching movement where initial concepts are covered outside of class, allowing class time for students to participate in a more comprehensive and thorough understanding of content. (Bergmann & Sams, 2014, Hung, 2015, Straw, Quinlan, Harland and Walker, 2015). This teaching pedagogy shifts, “learning into any time and place, not only being limited to class time.” (Roehl, Shweta & Gayla, 2015, p.45). Where, “today’s students can access online video resources, anywhere at their convenience.” (Halili & Zainuddin, 2016, p. 2).

Personalisation and Engagement Combined - JiTT

A technique that is created through this pedagogy is Just in Time Teaching (JiTT). In this strategy, the teacher reviews students’ understanding before class through formative assessments and, “adjusts the in class activities to address the deficiencies reflected in the assessments (Love, Hodge, Grandgenett & Swift, 2014, p. 320). Other formats ask students the question before class, ‘What did you find difficult or hard about the content in this video?’ The teacher is then able to begin class with these questions and work through any misconceptions that the students have. The JiTT approach adapts the content to where students’ understanding is at the moment of confusion. This strategy is, “a natural application of one to one teaching that is possible when students are working in class time.” (Roach, 2014, Kim, Kim, Khera & Getman, 2014). The student is able to clear up any confusion immediately and the, “instructor is able to monitor performance and comprehension,” (Lage, Platt, Treglia, 2000, p.37) which would be otherwise difficult in a traditional classroom.

Weaknesses of Flipped Learning

Teachers and students, within the Flipped Learning model, have indicated issues with the model around student completion of work, incorrect video content, poor quality video instruction and lack of preparation for this pedagogical shift. In order for this learning programme to operate, students need to have high levels of self management. It places, “more dependence on the student and their own learning,” for which some students are not yet ready (Peters, 2015, p. 6). A number of studies found that students in Flipped Learning environments expressed concern that the, “teacher was not teaching and they were just being told to Google it.” (Enfield, p. 22). Flipped Learning requires students to develop analytical skills where the teacher acts as a guide to direct them to potential solutions (Enfield, 2013, Kim, Kim, Khera & Getman, 2014), while working on collaborative tasks in class. The main challenge in beginning this programme is the amount of time to create videos/content that relate to their teaching topic (Tucker, 2012). When searching for video content already available, many teachers found that, “content was technically erroneous and did not relate to course learning outcomes to make them relevant to the programme,” (Peters, 2015, p. 8) requiring large amounts of time investment if completed by untrained teachers. As a result, many times teachers produce poor quality video content where students do not want to watch video content. Finally, access to technology can be another barrier particularly around access to resources which are predominantly in a digital format (Roach, 2014, Enfield, 2013, Bergmann & Sams, 2014). Many students can become frustrated if there are technical issues with out of class content, although teachers must provide an alternative if this is an issue. Although a range of studies have been completed, there is no specific evidence that, “Flipped Learning had improved student grades,” (Kim, Kim, Khera & Getman, 2014, p. 46) which needs to be taken into account if shifting to this teaching method.

https://goo.gl/i4sRYF

Conclusion

Flipped Learning is an approach to teaching that is growing in popularity throughout primary, secondary and tertiary education sectors by providing active learning experiences for students. In this reflection I have outlined five benefits to this approach and one area for continued development. In the past people may have scoffed at this approach due to the lack of data and research on its effectiveness on learning. However, the amount of research and peer reviewed literature being produced is continuing to grow. Flipped Learning, Flipped Classroom, the Inverted Classroom, will continue to re imagine the use of time, space and expertise in learning. If you are interested in this approach please review the bibliography for a fantastic range of research and feel free to comment below.

Bibliography

Bergman, J. & Sams, A., (2014). Flipped Learning: Gateway to Student Engagement. New York: International Society for Technology in Education.

Bolstad, R. & Gilbert, J. et al. (2012). Supporting future-oriented learning and teaching - a New Zealand perspective. Wellington: New Zealand Council for Educational Research. Retrieved from http://www.nzcer.org.nz/research/publications/supporting-future-oriented-learning-and-teaching-new-zealand-perspective

Dumont, H., Istance, D., & Benavides, F. (2010). The Nature of Learning. Using Research to Inspire Practice. Practitioner Guide from the Innovative Learning Project. OECD Centre for Educational Research and Innovation. Retrieved from: http://www.oecd.org/edu/ceri/50300814.pdf

Enfield, J. (2013). Looking at the Impact of the Flipped Classroom Model of Instruction on Undergraduate Multimedia Students at CSNU. TechTrends , 57(6), 14-27. doi: 10.1007./s11528-013-0698-1

Hung, H.T. (2015). Flipping the classroom for English language learners to foster active learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 28(1), 81-96. doi: 10.1018/09588221.2014.967701

Kim, M. K., Kim, S.M., Khera, O., & Getman, J. (2014) The experience of three flipped classrooms in an urban university: An exploration of design principles. The internet and Higher Education, 22,37-50. Doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2014.04.003

Lage, M.J., Platt, G.J., & Treglia, M. (2000) Inverting the classroom: A gateway to creating an inclusive learning environment. The Journal of Economic Education, 31(1), 30-43. Doi: 10.1018/00220480009596759

Love, B., Hodge, A., Grandgenett, N., & Swift, A.W. (2014). Student learning and perceptions in a flipped linear algebra course. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 45 (3), 317-324. Doi: 10.1018/0020739X.2013.822582

McLaughlin, J.E., Roth, M.T., Glatt, D.M., Gharkolonarehe, N., Davidson, C.A., Griffin, L.M., Mumper, R.J. (2014). The Flipped Classroom: A course redesign to foster learning and engagement in a health professions school. Academic Medicine, 89(2), 236-243. Doi: 10.1097/acm.00000000000086

Peters, M. (2015). Flipped Learning in an Undergraduate Engineering Class. Austrlasian Association for Engineering Education, 15 (6). 10-18.

Roach, T. (2014). Student perceptions towards flipped learning: New methods to increase interaction and active learning in economics. International Review of Economics Education, 17, 74-84. doi:10.1016/j.iree.2014.08.003

Roehl, A., Shweta, L., & Gayla, S. (2013). The Flipped Classroom: An Opportunity to Engage Millennial Students Through Active Learning Strategies. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences, 105 (2), 44-49.

Straw, S., Quinlan, C., Harland, J. and Walker, M. (2015). Flipped Learning: Research Report. London: Nesta.

Zainuddin, Z., & Halili, S., (2016). Flipped Classroom Research and Trends from Different Fields of Study. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 17(3), 36-53.

No comments:

Post a Comment